#2 Silent Display

Battleship Potemkin (1925) BSO by Edmund Miesel

Bronenonsets Potyomkin (Battleship Potemkin, Russia, 1925) 65' B/W. Production: Goskino. Address of Sergei M. Einsenstein. Script: Sergei M. Einsenstein, Nina Agadhanova-Shutko. Photograph by Eduard Tisse, V. Popov. Music by Edmund Meisel. Interpreters: Antonov, Alexondrov, Vladimir Barksy, Levshin, Gomarov, Strauch.

"It is sometimes strange that in matters of practice in sound film I seem to be the last to arrive at the finish line. At the time of its inauguration I was the youngest of all the directors and now I seem to be the last to take part in the work. But on closer examination I see that this is not so. My first work on sound film was in 1926 and in connection (again!) with Potemkin.

Potemkinat least in its foreign circulation, had a score expressly written by the composer. Edmund Meiselwho had written music for other silent films. This was nothing unusual, since there are many silent films that have special scores, as well as music had been used for the filming of some movies; for example. Ludwig Berge had filmed Ein Walzertraum about music by Strauss.

But the way in which the score was composed for Potemkin was no longer so usual, for it was written as we work now in sound film, or rather, as we should always work, in creative friendship and friendly creative collaboration between composer and director. So it happened in MeiselDespite the short time he had for the composition and the short visit to Berlin to meet him. He immediately agreed to leave aside the purely illustrative function, which was common in the musical accompaniment of that time (and not only that time), and to give importance to certain "effects", particularly in the "machine music" in the last part. My only categorical request was the following: not only to reject the usual melodic music in the shot of "Encounter with the square" and to rely only on a rhythmic repeated percussion sound, but also to give substance to this request by establishing in the music, as in the film, a change to a new quality in the sound structure at the decisive place.

So it is that Potemkin was the film that stylistically crossed the boundaries of the "silent film with musical illustrations" reaching a new sphere, the sound film, in which the true models of this art form live in a unity fused in musical and visual images of the work of an auditory-visual image at the same time. It is exactly due to these elements that, anticipating the potentialities of an internal substance for the composition of a solo film, the sequence of "Meeting with the squadron" (which together with "The Odessa bleachers" has caused such a transforming effect abroad) deserved a prominent place in the anthology of cinema.

It is of particular interest to me that the overall construction of the Potemkin to maintain in the music all that was striking in its pathetic construction, the condition of a qualitative step, which, as we have seen before, was inseparable from the organism of the theme.

The silent one Potemkin teaches a lesson to the sound film, stressing again and again the position that an organic work must be permeated in all its meanings by a simple law of construction, and that in order not to be something "offstage," but an integral part of the film, the music must also be governed not only by the same images and themes, but also by the same basic laws and principles of construction that govern the work as a whole.

It didn't take long before I was able to realize this, to a high degree, in my first sound film, Alexander NewskyThis was possible thanks to the collaboration of such a brilliant and wonderful artist as Sergei Prokofiev (1939)".

Film theory and technique, by Sergei M. Eisenstein. Published by Ediciones Rialpcollection Film BooksMadrid, 2002. Pages 231 and 232.

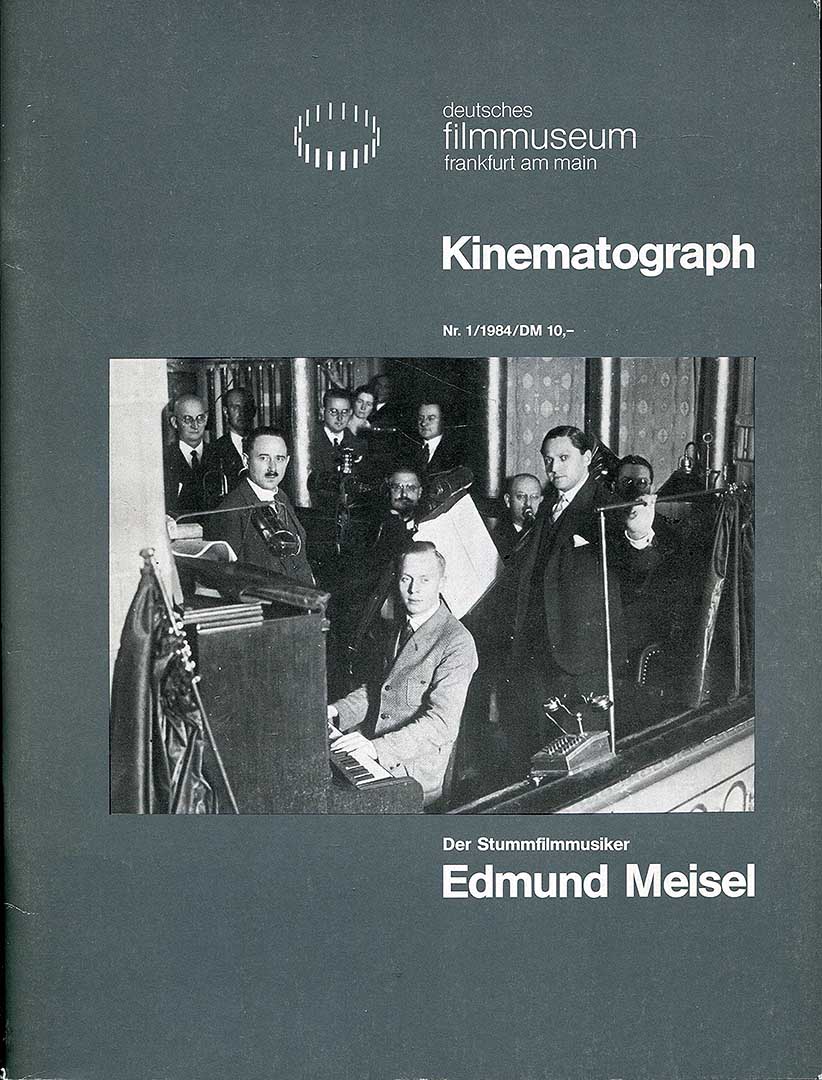

"Edmund MeiselAustrian violinist of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, composer for the Deutsches Theatre with Max Reinhardt and for Prometheus-FilmHe wrote the music for the German distribution versions of the Potemkin and October and for Berlin."

Symphony of a great city, by Walter RuttmannGermany, 1929.

"The film was banned in many countries, and in some countries its editing was even manipulated to prevent it from conveying its revolutionary message. The historian Román Gubern He said: "The Swedish distributor encountered problems with the censors, who would not authorize the film. As he did not want to lose the investment he had made, he redid the editing. That man took the shots of the firing squad, of the repression of the officers, and put them at the end, so that the rebellion would not triumph. And so Battleship Potemkin was shown in Sweden. It circulated as a counter-revolutionary film, whose moral was that he who revolts, gets it."

JEWELS of the Mute Cinema, by Vicente Romero. Published in Editorial Complutense, Madrid, June 1996. Page 211.