Uncertainty Theory #12

The Lithophone and The Kybalion Principle of Vibration

MUSIC

Lithophone Demonstration by Mårten Bondestam.

The Richardson Musical Stones - improvisation Lithophone Looped#1.

L'Ocelle Mare live presentation at El Pumarejo de Vallcarca 30-11-2016

LITHOPHONE

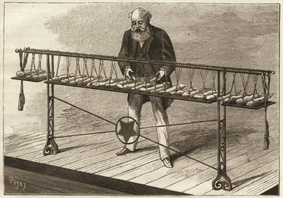

The lithophone is a rudimentary instrument built with stones, as the word itself says (lito= stone, fono= sound), it is considered a predecessor instrument to the bell. It is considered an instrument that has crossed different times and cultures, according to some experts its use has been as extreme as from children's games to secret rituals. In the ancient Chinese culture of the Shang dynasty, the first instruments made with stones are already described. In Europe, there is no record of a similar instrument until the early twentieth century, when Antonio Roca y Várez designed and built the first modern lithophone.

SOME EXAMPLES BY COUNTRY

ANGOLA

The people of Chokwe use stone bells called sango.

ARGENTINA

In Santa Rosa de Tastil, Argentina, there is a special quartz from which lithophones have been made locally. "Tastil" apparently means "sounding rock". An example of the lithophones can be found in the local museum.

AUSTRIA

At the beginning of the 19th century, Franz Weber built an alabaster instrument he called Lithokokymbalon.

AZERBAIJAN

The Gobustan (Kobustan / Qobustan) caves contain ancient cave drawings that include depictions of dances. There is also a rock that emits a deep resonant sound when struck, known as gaval-dashy (apparently meaning "tambourine stone") and it is popularly believed that dancing took place to the accompaniment of the sound of the stone.

BOLIVIA

The people of northern Potosí in Bolivia apparently used resonating stones whose sound was apparently sustained by them as manifestations of the presence of the demon, Supay, trapped within them.

BORNEO

The Sea Dayak people in Borneo have used stone bells which they refer to as kromo.

CHAD

Small stones are used in the rattle known as Yondo, which comprises a pipe, usually made of metal.

CHINA

There are many examples of suspended stone bell bars in China. The original examples found in archaeological finds are made of marble, although later ones tend to be made mainly of jade. They were generally used for ceremonial purposes. Some of these date back thousands of years. The bian ch'ing or bian'qing usually consists of a set of sixteen or thirty-two L-shaped tuned slabs, which are suspended on a large frame and struck on their long side with wooden mallets or cushioned sticks. Image below courtesy of Dr. Kia C.NgUniversity of Leeds.

COLOMBIA

The Murui Muinane people of the La Chorrera region have long traded locally quarried granite. They appropriated a large slab for use as a gong that they traditionally used to communicate across distances and rituals.

ECUADOR

Apparently, the National Museum owns a lithophone, although details are hard to find.

ENGLAND

In the 18th century, rocks found in the riverbed at Skiddaw in the Lake District were found to possess a particularly sonorous quality. Peter Crosthwaite, who had opened his own museum in Keswick, assembled a set of musical stones in 1785, some of which were already in perfect tune, the rest being tuned by cutting the stone. They can now be seen in the Keswick Museum & Art Gallery, where the image below was taken. In the years that followed, several people began making musical instruments using the stone, known as hornfels or spotted shinbones, meticulously tuning them by cutting them into slabs of varying lengths and laying them horizontally. The best known, and the largest, was built by Joseph Richardson, he called it the Rock Harmonicon, and subsequently made a career on it touring Britain and abroad giving recitals. The instrument can now be seen and played at the Keswick Museum. Also widely known, emanating from the same area but finding success upon moving to the United States, was the Till Family Rock Band, formed by Daniel Till and his two sons, James and William. Part of their instrument can be seen in the Metropolitan Museum. New York. Other examples of Skiddaw lithophones can be found, including one commissioned by John Ruskin, now in the Ruskin Museum in Coniston. A new telephone is currently under construction and will be housed in Ruskin's former home, Brantwood, on the edge of Lake Coniston. In 19th century Yorkshire, a man named Neddy Dick, of Keld, upper Swaledale, was known for his extraordinary collection of musical instruments which included a collection of rocks that he played by striking them with various implements. Many of these he obtained by scouring the Swale riverbed.He never achieved the wider success enjoyed by the Richardsons and the Till family: a country tour was planned, but sadly he died a few days before his debut.

ETHIOPIA

The use of stone bells, known as a pin, has been adapted for Christian use in the Coptic church and can be heard, for example, in one of the monasteries on an island in the middle of Lake Tana. They hang from a rope and are apparently used functionally, as, for example, a dinner gong.

FINLAND

In the Karelia region, on the border of Finland and Russia, rock gongs have been found near petroglyphs or carved in stone. This suggests that they were used ceremonially, probably by Saami people.

FRANCE

There are several examples of sounding stones in Brittany. At Menec, near Carnac, there are some standing stones known as "pierres creuseso". "hollow stones" because of its ring. It is quite possible that the sound of the stones was incorporated into rituals intended for the stones placed. At Le Guildo, on the edge of the Arguenon estuary, there are some rocks that are well known locally for their propensity to sound when struck. A folklore has accumulated around them. At the shrine of St. Gildas Cave, near Pontivy, where, until his death in 540 AD, the Welsh missionary hermit who gave him his name used a rock gong to summon his small congregation to mass. The gong may have been used previously in pagan ceremonies It can still be seen and, a couple of miles away, in the church at Bieuzy, there is another rock gong.

In Dordogne there are a number of caves containing prehistoric paintings very close to the stalactites that sound when struck and show evidence of considerable use.

In the 19th century, amateur scientist Honoré Baudre spent more than thirty years searching for flint pieces suitable for what he called his geological piano. He was invited to play at various concerts and exhibitions in France and elsewhere in Europe, including several concerts in Great Britain. A translation of a contemporary French article about him appears elsewhere on the site under Articles.

GERMANY

The composer Carl Orff (1895 (1895-07-10) - 1982 wrote for the lithophone and his student Klaus Becker-Ehmck had him build one. The instrument, which he referred to as Steinspiel, was used in particular in his opera Antigonae.

GUINEA

Several examples of resonating rocks have been documented. These appear to have been used for communication, for public announcements and as warning signs of impending danger.

HAWAII

Prior to the introduction of the guitar and ukulele into Hawaiian music in the early 1880s, most of the instruments used to accompany traditional hulas were percussion instruments. These included pairs of stone castanets consisting of round, flat pieces of basaltic lava, played by hula dancers. Two of these pairs are housed in the U.S. National Museum of Music in Vermillion, South Dakota.

ICELAND

Icelandic composer Elias Davidsson has used and written about lithophones.

The band Sigur Rós has also used lithophones and it is suggested that their modern use follows an ancient tradition of lithophones found in the country. They are made of isotropic basaltic stones that, as a result of climatic changes, have split into thin sheets or slabs.

INDIA

There are ancient examples in Orissa, in southern India, of rocks and boulders that emit sonorous sounds when struck and which, because of their proximity to rock carving sites, suggest that they were used musically. They are believed to date back to Neolithic, or late Stone Age times (several thousand years B.C.). Other sites in southern India also have evidence of early use of resonant rocks. Some, cited by Catherine Fagg at Rock Musicare found at Gulbarga, although it is not clear to what extent they were used to any significant extent. There is more evidence in the work of Nicole Boivinwho has investigated sites at Sangana-Kupgal, near the town of Bellary in Karnataka. Here there are resonant rocks with clear evidence of cup marks to suggest rhythmic play and are located next to petroglyphs, drawings incised into the rock.

From more recent but still ancient times, there are many temples in India built with stone pillars that resonate with different tones, turning the whole building into a musical instrument. Examples can be found in Hampi (Karnataka), Tadpatri and Lepakshi (Andhra), Madurai, Vaishnavite shrine in Tirunalveli (or Tirunelvelei), Alagar Koil, Tenkasi, Curtalam, Alwar, Tirunagari and Suchindram in Tamil Nadu.

JAPAN

Suspended bell bars can sometimes be found in Buddhist temples and are very similar to those in China. It is more common for these to be metal, but the earliest examples were made of stone. Stone is also used in wind chimes.

JAVA

It is believed that gongs or bonangs in Java were originally made of stone: examples have been discovered at several sites in East and Central Java.

KENYA

Rock gongs are found in several places: in central Kenya, near Embu, on the island of Mfangano in Lake Victoria, in the Kilifi district near the coast and elsewhere. Sometimes these have had a ritual, sacred significance, in other places children use them in a more playful way.

KOREA

Like Japan, Korea adopted the Chinese form of stone bell bars for ceremonial use. In Korea, these are known as pyen kyang and comprise sixteen L-shaped slabs suspended within a frame.

LIBERIA

There are several examples of stones that are used as a simple percussion material, without being characterized by any particular quality of tone. The British Library's National Sound Archive has recordings of songs from Liberian plays accompanied by stones.

MALI

Apparently, the Dogon people of Mali have used lithophones. In 1966, the filmmakers Jean Rouch and Gilbert Rouget made a film Batterie Dogon. Éléments pour un étude de rythmes on their use. There are several examples of resonant rocks, some of which may have cultural significance.

MALAYSIA

Batu Gong, near Tambunan in Malaysia, is apparently known for its musical rocks. They are large pieces of stone lying on the ground and each one emits a range of different tones and pitches depending on where it is struck. Groups of local people gather to play tunes on them (possibly for the benefit of passing tourists). What their past cultural significance might have been is unclear.

MEXICO

In Oaxaca, in caves associated with the Mixtec people, there are a number of stalactites, stalagmites and columns that appear to have been used for musical purposes. These caves had a particular cultural significance and were used for various rituals. In one cave in particular, Las Ruinas, there are speleothems with indentations and marks that suggest they were percussively struck.

MICRONESIA

In Pohnpei, Caroline Islands, there is a tradition of grinding kawa root, an intoxicant widely used throughout the region, using stones on a large resonant basalt plate. The preparation becomes a musical performance as the resulting rhythms take over the work at hand.

MONGOLIA

There is a now rarely heard Mongolian lithophone known as the shuluun tsargel , whose stones are suspended by a cord in a frame. The CD Musique et Chants de Tradition Populaire Mongolie Grem G7511 contains a track played on an instrument made up of fourteen stones by a musician from Bayan Khongor in southern Mongolia.

NEW ZEALAND

Stones have been used in a variety of ways in Maori music. Unusually, stone (along with bone and wood) has been used to make flutes that mimic the sound of birds. In particular, the stone koauau is used to replicate the bell-shaped notes of the bird known as kokako. Stone has also been used to make bullroarers in which "the spirit of the player travels down the cord to create sound, which then travels on the wind to carry the player's words and dreams to listeners around the world."

NAMIBIA

Examples of resonant rocks have been found with multiple cup marks suggesting that they have been struck repeatedly, most likely in a rhythmic and musical manner, although the exact nature of their use no longer seems to be known.

NIGERIA

The Yoruba people have a history of using lithophones, but the best documented examples of musical stones in Nigeria are the multiple rock gongs upon which Bernard Fagg wrote in the 1950s and later documented in his widow's book Catherine "Rock Music". (1997). The most notable are found at Birnin Kudu in Kano State. These rock gongs have been used for communication, ritual and recreational use. They may also have been used for ensemble musical performances.

PORTUGAL

The painted cave of Escoural in Evora is similar to those of Dordogne in France, as it combines cave paintings with stalactites that show signs of having been repeatedly struck. This suggests evidence of rituals dating back to Paleolithic times.

RUSSIA

Alla Ablova of the Petrozavodsk Conservatory in Russia is an authority on ancient lithophones discovered in various parts of the world. He has written in particular on some that appear in various legends and folk songs of the Karelia region of Russia and in Saami folktales.

SCOTLAND

There are several sounding stones in Scotland, at least some of which had ritual significance in ancient times. One of them, "Arnhill"also known as "Ringing Stane" and "Haddock Stone" located near Huntly in Aberdeenshire, forms part of a stone circle. Others include Johnston Stone, also in Aberdeenshire, and The Ringing Stone or Clach o'Choire on the island of Tiree in the Inner Hebrides.

SOUTH AFRICA

Catherine Faggin his book Rock MusicThe author mentions several stones in the Britstown district of central South Africa, but was unable to establish their level of importance within the community. In many parts of the world, there is sometimes a reluctance to talk about the sound of the stones, possibly because of their sacred quality, and even their whereabouts remain a local secret.

SUDAN

Rock gongs are found on the west bank of the Nile and were also documented by Bernard Fagg. One appeared in the first documentary series of the BBC Lost Kingdoms of Africa and it was suggested that many other gongs, whose use dates back to 5000 BC, have been discovered there in the Nubian desert.

SUMATRA

In West Sumatra there are some ancient musical rocks known as talempong batu that can be seen in Nagari Talang Anau. From photographs they look a bit like those found in Vietnam. It seems likely that they were the predecessors of the metal gongs known as talempong found in the same region. It is unknown how old they are or what social function they may have had originally, although they would certainly have had a ceremonial use. Apparently, talempong batu are still considered locally to possess spiritual powers and it is said that in the event of an impending disaster, the stones will emit strange and bizarre noises.

SWEDEN

On the island of Gotland is a granite boulder that rings with cup marks, indicating a probable repeated reproduction. It is reputed to have been used in ancient times as a sacrificial stone and a pagan altar.

TANZANIA

The well-documented rock gong shown below is located at Moru Koppies in Tanzania's Serengeti National Park. Unlike some rock gongs that are part of a larger rock formation, this one stands alone. Cup marks, resulting from years of being pounded, are clearly visible and cover each side. It is uncertain how it was used, although it may have played a role in Maasai culture. There are many other examples of resonant rocks found in Tanzania, some of which may have been used in ancestral and rain ceremonies.

IR

The Kabiyé people, from a region in northern Togo, a small West African state that lies between Benin and Ghana, play musical stones for ceremonial and ritual purposes. The playing of music is strictly linked to the agricultural seasons and these musical stones can only be played for a short period after the harvest between November and January. The stones, known as pichanchalassi, are placed on the ground, usually, it seems, in a set of five, each with a different pitch, and struck with another smaller stone. Several tracks of the pichanchalassi playing can be heard on Ocora's CD Togo.

UGANDA

Along with Nigeria and Sudan, Uganda can boast a number of natural rock gongs. These have been documented in the book Rock Music from Catherine Fagg.

They appear to have sometimes been used ritually and their whereabouts are sometimes a local secret. More profanely, they are often used by children as a play area. In 2007, composer Nigel Osborne undertook a commission in collaboration with London Sinfonietta based on the sounds of rock gongs on Lolui Island located in Lake Victoria.

UNITED STATES

VIRGINIA

The Great Stalacpipe Organ, Luray Caverns, Shenandoah National Park. The instrument is the creation of Pentagon mathematician and scientist Leland W. Sprinkle and was built in 1954. Playing the keyboard triggers rubber-tipped mallets, which strike stalactites in the surrounding caverns, carefully chosen for the accuracy of their pitch. The organ claims to be the largest musical instrument in the world.

MINNESOTA

The quarry at Pipestone, Minnesota, mentioned by Longfellow in "The Song of Hiawatha."is the source of a soft clay stone carved by the Sioux into ceremonial pipes. They also created musical instruments from pipestone. This rare example of a non-percussive lithophone is in the National Music Museum in Vermillion, South Dakota.

PENSILVANIA

Resonant rocks are a well-known feature of the landscape near Easton. It is not known to what extent these had any ancient ritual significance. Their main cultural role comes from tourism.

UZBEKISTAN

Here they play stone castanets known as qayraq/kayrak or "black stones"two in each hand, to accompany the dance.

VENEZUELA

In the early 20th century, several archaeological excavations in South America unearthed what were thought to be examples of stone percussion. A burial cave at Niquivao in Trujillo, Venezuela, contained rectangular serpentine slabs with incisions that suggested they may have been suspended for use as a type of bell or gong.

VIETNAM

Many clusters of stones of different pitch have been found in Vietnam, indicating that they were being used musically thousands of years ago. The first of these was discovered by a French archaeologist. Georges Condominas in 1949. Some of Vietnam's minorities, such as the M'nong, most of whom live in the central highlands, have continued to use these stones. Although not central to traditional Vietnamese music as it is presented today, their place is recognized and some musicians have built their own modern versions and continue to play them. The Vietnamese name is dan da. The ancient set of stones seen in the photo below was seen in a music store in Hanoi. An article by Mike Adcock about a trip to Vietnam in search of musical stones appears in the Articles section of this site.

WALES

The Pembrokeshire village of Maenclochog in Dyfed lies south of the Preseli Hills. Its name is Welsh for stone ringing, a reference to two large stones that adorned the landscape. That was until the late 18th century when they were dismantled to build roads in defiance of the wishes of the local population. It seems that there are still other sounding stones in the region, some with cup marks.

ZIMBABUE

Several rock gongs and resonating stones have been documented in Zimbabwe. As in other parts of Africa, some of these appear to have been used as a means of communication over long distances. Others have sacred significance and are believed to speak the voices of ancestors. Near Muzondo, in the Musombo and Chiramba region, ensemble musical performances have been documented, using mujejejeje, the Shona word for musical stones.

Principle of Vibration of The Kybalion:

"Nothing is still; everything moves; everything vibrates."

This principle embodies the truth that everything is in motion, that nothing remains motionless, both of which are confirmed by modern science, and each new discovery verifies and proves it. And yet this hermetic principle was enunciated hundreds of years ago by the Masters of ancient Egypt. This principle explains the differences between the various manifestations of matter, of force, of mind and even of spirit itself, which are but the result of the various vibratory states. From the ALL, which is pure spirit, to the grossest form of matter, everything is in vibration: the higher the vibration, the higher its position on the scale. The vibration of the spirit is of infinite intensity; so much so, that it can practically be considered as if it were at rest, just as a wheel turning very rapidly appears to be without motion. And at the other end of the scale there are forms of very dense matter, whose vibration is so weak that it also seems to be at rest. Between both poles there are millions of millions of degrees of vibratory intensity. From the corpuscle and the electron, from the atom and the molecule to the star and the Universes, everything is in vibration. And this is equally true of the states or planes of energy or force (which is but a certain vibratory state), and of the mental and spiritual planes. A perfect understanding of this principle enables the Hermetic student to control his own mental vibrations as well as those of others. The Masters also employ this principle to conquer natural phenomena. "He who understands the vibratory principle has attained the scepter of power," has said one of the most ancient writers.

Sources: http://www.lithophones.com/ http://www.wikipedia.com