Uncertainty Theory #23

On listening in human pre-existence and sound or holophonic immersion. Part II.

Audios:

-Oliveros Sonic Meditation (2017) - ~Environmental Dialogue~ for four voices and four minimoogs (track 2) - Petridisch.

-Oliveros Sonic Meditation (2017) - XVI For Six Voices (track 1) - Petridisch

-From Now On - Pauline Oliveros.

Life sings and improvises from molecules to galaxies. Sound speaks to us, even if it has nothing specific to say. The melodies of the world are what they are. Nothing less, nothing more. We must not be afraid to listen (David Rothenberg).

Darkness enables deep, reflective isolation. By closing our eyes we can become aware of a wide variety of inner sensations and may be able to establish a connection with higher states of mind. A blindfold around the eyes allows us to abstract ourselves even more from phenomenal reality, from visual matter, making our appreciation of sounds much more direct. (Francisco López)

My most profound initiation into the powers of the bass occurred with the sound of the Aba Shanti-I sound system one evening in 1990 at the Notting Hill Carnival in East London... Standing surrounded by the sound system speakers, at one point the bass became so loud that my vision was blurred by the amplitude of its vibrations, the fluid in my eyeballs moving with the sound. I was enveloped in a haze as the sensation of being a body separate from my surroundings and other bodies began to dissolve. Marcus Boom.

"When we enter the world of a sound, it is a new world. When we prepare to leave that world, we expect to return to the world we had left. However we find that when that sound stops, or when we simply leave the area in which it takes place, the world we enter is not the old world we left but a new one. This is partly because we experience the old world with the added ingredient of the sound world [...] When you enter a new world, of a sound, or any other world, you never leave it." La Monte Young.

Summary concepts

Listening has to do with the relational, with communication.

Extremely low frequencies, or even below the audible range, approximately 20 Hz, are present in natural phenomena such as storms or earthquakes and in certain cultures are often associated with feelings of "danger, sadness or melancholy" becoming a very effective procedure, especially for some composers of the nineteenth century who believed in "absolute" music as a language capable of expressing feelings otherwise inexplicable. It is common to find frequencies of 30.87 Hz -which corresponds to the note B0- for whose execution it was necessary to use double basses with extension or with five strings, a limit soon surpassed by the Octabass included in works by Berlioz, Borodin, Brahms, Mahler or Stravinsky, among others. Although the first prototype of this three-stringed instrument built by Jean-Baptiste Vuillaume in 1849, which is about 4 meters high, did not provide frequencies lower than those achieved by the extended double bass, according to the specifications of Hector Berlioz himself in the update published in 1855 of his Grand traité d'instrumentation et d'orchestration modernes, some later versions reach 16.25 Hz (C0), the same limit frequency of the Imperial piano of the Bösendorfer firm. A special model with 9 additional keys in the lower register was commissioned by Busoni in 1900 in order to adapt some of the works composed for organ by J. S. Bach that included this infrasonic tone.

An experiment carried out in 2003 by Hertfordshire University and the National Physical Laboratory linked these frequencies emitted by the organ with a feeling of "intensification of the emotional state of the listener" and with feelings of anxiety or exaltation caused by the increase in heart rate that could contribute to fuel religious fervor. And even psychologist Richard Wiseman has suggested the possibility that some phenomena associated with paranormal perceptions may have their origin in exposure to constant vibrations around 19 Hz reinforced by standing waves in the places where they occur.

The association of the subsonic with the supernatural also appears in certain shamanic practices, following hypotheses of archaeacoustics about the properties of some spaces capable of drastically amplifying the sub-bass of percussion instruments. And much more evident is the use of the Uher-buree in the Buddhist repertoire, a 5-meter trumpet widely used in Himalayan areas projecting its sound towards "the mountains to produce a tremendous echo" and "infrasonic frequencies" to which is attributed the power to "unite heaven and earth, light and darkness".

In fact this symbolic idea of low frequencies as a link between "heaven and earth", between the immaterial and the material, the intangible and the tangible, is very close to how we experience sounds that are at the lower threshold. As Jeremy Gilbert and Ewan Pearsons explain, "the difference between matter and energy can be expressed in terms of a simple difference between the speeds at which particles vibrate, i.e., particles that generate matter vibrate more slowly than those that generate energy." Thus, as we descend in height the sound becomes denser, the lower it is, the more "materiality" it possesses, the more omnidirectionality it acquires and the more "real" its presence is, intensifying the immersive sensation. A phenomenon that musical styles such as Dub have intentionally abused to delimit the dance hall as a "ritual" space in which "the bass acts as a pressure drop [...], the lower frequencies become spectral walls of underpressure that bend you and put you in colossal pockets of solid air, hot embankments that emerge to surround you".

This organic relationship of the viewer with the space conceived as a vibrant and enveloping architecture has been a central line of work in the fields, not always differentiated, of music and sound art in recent years, as exemplified by the career of the American Mark Bain. Marked by a family tradition linked to architecture, Bain seeks the immersive effect by transforming buildings into vibrant structures capable of emitting sound, placing us in the center of a resonant environment, as if it were the "inside of a bell". His experiments have a double focus, attending to both the capacity of matter to produce sound and the potential of sounds to create "invisible architectures", habitable sculptures that you can feel "even if you don't see anything, without the need to use any kind of virtual reality glasses, just by entering and feeling its presence as if it were a ghostly entity". Some of the studies on feedback and resonances by Alvin Lucier, John Driscoll, Raviv Ganchrow and ILIOS, or works such as Panels (2010) by Paul Devens, are also close to this line of experimentation with the acoustics of spaces.

Perhaps one of the most representative cases of this desire to build "immersive architectures" is the well-known Dream House by La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, in which the use of pure tones is combined with simple but effective visual elements, a combination that, with the same transformative purpose, we also find in the works by the Belgian artist Ann Veronica Janssen, in the LSP (Laseer/Sound Performances) by Edwin Van der Heide, in works such as Filmachine (2006) by Keiichiro Shibuya and Takashi Ikegami, db (2000) by Ryoji Ikeda, Syn chron (2004) by Carsten Nicolai or ZEE (2008) by Kurt Hentschlager, to mention just a few more recent examples.

But in the strictly sonic realm, the interesting thing about the Dream House is that it makes a radical use of duration as a main resource to create immersive states. First located in 1966 in a SOHO loft, it functions simultaneously as a composition, a sound installation and a performative space that has occupied different locations for extended periods of time, becoming an "environment with a constant sound and light frequency and occasional singing", capable of emitting "for ten, a hundred, or even more years, a constant sound, which would become not only an organism with its own life and tradition, but with the ability to feed on its own momentum".

The sine waves produced by a series of oscillators at different volumes organize a space in which the intensity of the sound creates multiple areas of pressure, such that "the different frequencies generate an environment where the volume of each will vary audibly at different points in the room if they are sufficiently amplified [...] This phenomenon [...] makes the listener's position and movement through the space part of the composition [...] allowing him to actually experience sound structures naturally as he explores it". Young thus proposes an alternative to the practices of his minimalist contemporaries based on rhythmic ostinatos by intensifying the sense of flow by dilating beats with extended drones, a device that often produces the sensation of "being explicitly immersed in a fog of sound". The result is a compositional work not based on a quasi-linguistic formalism of hierarchies -motifs, half-phrases, phrases, blocks...-, but focused on the very ontology of acoustic perception, perhaps the most important paradigm shift of the 20th century in the context of sound creation. The waves tuned according to just intonation that inhabit the Dream House provoke sensations that we cannot appreciate when we listen to tonal relationships based on equal temperament, standardized since the 18th century. The resulting harmonic proportions cause our ear to be activated differently from what we are used to.

In this sense, the work carried out by some artists with the Otoacoustic Emissions, specifically with those known as EOAPD (Product of Distortion), are particularly interesting, exploiting not only the resonances of the space that surrounds us, but also those inside our ear. This phenomenon already documented by Giuseppi Tartini in his Tratato di Musica Secondo la Vera Scienza Dell'Armonia (1754) under the term Terzo Suono, and mentioned by several acoustic physicists since then, occurs when under certain conditions the sum of two frequencies stimulates the basilar membrane causing our ear to emit a third signal that is not in the original source, but we hear it as if it were produced inside our head. Among the artists who have systematically experimented with this phenomenon is the composer Maryanne Amacher, who has worked on different aspects of what she herself defined as "perceptual geographies". Amacher's intention is to provoke in the listener "vivid experiences of contributing this other sonic dimension to the music her ears are producing20". An example of this use of the "third tone" can be heard on the album Sound Characters: Making the third ear, released by the Tzadik label in 1999. At an appropriate volume, its reproduction "causes your ears to act as a neurophonic instrument" and you feel how "the music comes out of your head, comes out of your ears, is born from them, adding to and converging with the tones in the room "21. Following the same principle Jacob Kirkegaard has realized his work Labyrinthitis (2007) for the Medical Museion in Copenhagen. Here the Danish artist starts from recordings of such emissions made inside his own ears, composing a work in which the resulting tones are reinforced to create a succession of derivative EOAPD in the form of a cascade of descending tones, forming, at the same time, a kind of symbolic spiral that recalls the internal design of the cochlea. This generates the expansion of the auditory space towards the interior, provoking a sensation of intense listening while we feel our own emanations and we become one more piece of the compositional framework. In this search for the overflow of the ear, as well as conventional reproduction systems, is also one of the latest works of composer Ben Vida for the PAN label, esstends-esstends-esstends (2012) with which he tries to "escape the stereo image and create an active listening space of expanded spatialization. Using the combination of just intonations to produce different tones and harmonic distortions, sonic materials are created that emanate from both the speakers and the inner ear22". Although starting from a different physical hearing capacity, bone transmission, some artists have sought to provoke similar sensations of inner listening as an immersive resource. An example of this other practice would be Laurie Anderson's Handphone Table (1978) or Lynn Pook and Julien Clauss's Stimuline (2008) audio-tactile concerts.

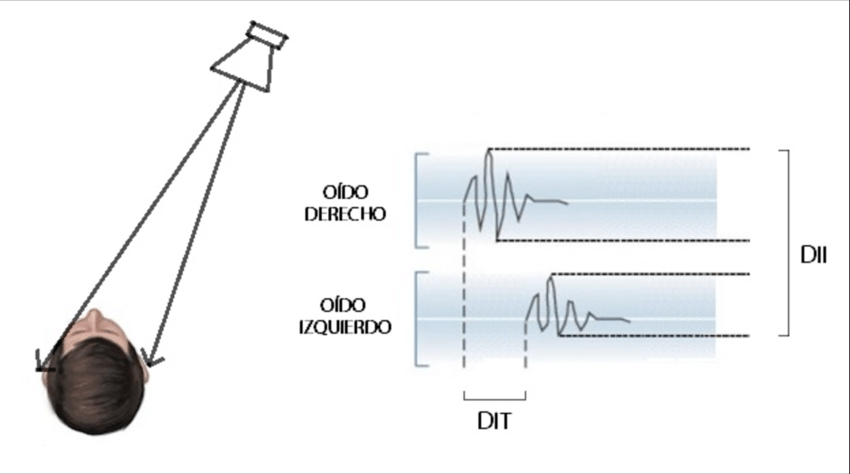

In addition to extremely low, long and intense sounds and the use of phenomena such as otoacoustic emissions or bone transmission, another of the most widely used immersive resources is spatialization. Although we find several examples throughout the history of music, it is in contemporary practices, and especially in those using electroacoustic reproduction systems, where it acquires a significant degree of sophistication, turning position in space or displacement into relevant compositional variables.

To a large extent these environments pose a reflection on the dematerialization of architecture linked to the idea of experience and the transformation of an environment. Architecture understood as a medium defined by events and not as an inert construction, a recurring idea evidenced when these spaces are referred to as "living beings". This idea of aural architectures is also present in the minimalism of Bernhard Leitnert's installations -Sound Lines (1972), Narrow Sound Space (1974), Sound Cube (1980), ...-.

Thus the suggestive power of immersive experiences goes, or should go, beyond the mere gimmicky amazement supported by the spectacularity of the media used, aspiring to offer a transformative axis, knowledge through sensory experience, expanding our listening beyond the transitory event as La Monte Young explains again:

"When we enter the world of a sound, it is a new world. When we prepare to leave that world, we expect to return to the world we had left. However we find that when that sound stops, or when we simply leave the area in which it takes place, the world we enter is not the old world we left but a new one. This is partly because we experience the old world with the added ingredient of the sound world [...] When you enter a new world, of a sound, or any other world, you never leave it."

In addition to extremely low, long and intense sounds and the use of phenomena such as otoacoustic emissions or bone transmission, another of the most widely used immersive resources is spatialization. Although we find several examples throughout the history of music, it is in contemporary practices, and especially in those using electroacoustic reproduction systems, where it acquires a significant degree of sophistication, turning position in space or displacement into relevant compositional variables.

To a large extent these environments pose a reflection on the dematerialization of architecture linked to the idea of experience and the transformation of an environment. Architecture understood as a medium defined by events and not as an inert construction, a recurring idea evidenced when these spaces are referred to as "living beings". This idea of aural architectures is also present in the minimalism of Bernhard Leitnert's installations -Sound Lines (1972), Narrow Sound Space (1974), Sound Cube (1980), ...-.

Thus the suggestive power of immersive experiences goes, or should go, beyond the mere gimmicky amazement supported by the spectacularity of the media used, aspiring to offer a transformative axis, knowledge through sensory experience, expanding our listening beyond the transitory event as La Monte Young explains again:

"When we enter the world of a sound, it is a new world. When we prepare to leave that world, we expect to return to the world we had left. However we find that when that sound stops, or when we simply leave the area in which it takes place, the world we enter is not the old world we left but a new one. This is partly because we experience the old world with the added ingredient of the sound world [...] When you enter a new world, of a sound, or any other world, you never leave it."